James Peter Moffatt

James Peter Moffatt is an award-winning composer, record producer & musician who has scored numerous award-winning international films, working alongside the likes of Academy Award and BAFTA winning Ben Wilkins (Star Trek, Whiplash, The Sopranos) and Ken Scott (The Beatles, David Bowie).

He is a Senior Lecturer at Leeds Conservatoire, with a focus on Film Music Composition and Industry Studies, teaching across all three years of the BA Film Music Degree as well as the Foundation Year.

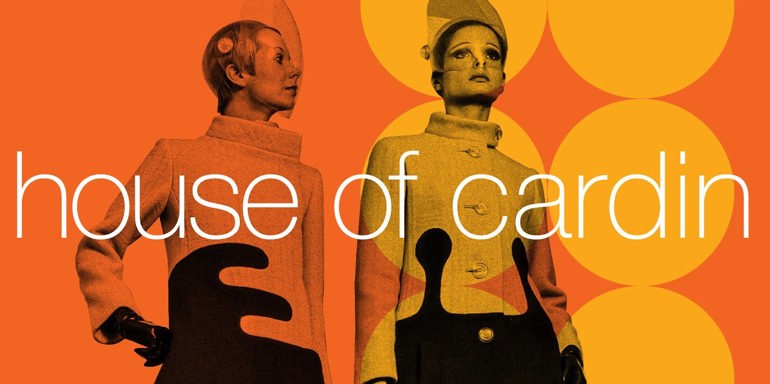

James has received recognition and critical acclaim for his most recent contribution to House of Cardin, a feature documentary chronicling the life and design of fashion icon Pierre Cardin.

You recently wrote music for the feature documentary House of Cardin chronicling the life of Pierre Cardin. Can you provide some background to the film?

'House of Cardin' is a rare peek into the mind of a genius, an authorised feature documentary chronicling the life and design of Pierre Cardin. A true original, Mr. Cardin has granted the directors exclusive access to his archives and his empire, and unprecedented interviews at the sunset of a glorious career. For those not aware, Pierre Cardin is an Italian-born French fashion designer known for his avant-garde style and his Space Age designs.

The film, which documents his life and designs, premiered at Venice Film Festival in September 2019 with a then 97-year-old Cardin in attendance. Having completed its festival run, the film is now beginning to roll out internationally in selected theatres as well as via video on demand services in response to the global pandemic. On Monday 21st of September 2020, the European theatrical premiere of the film took place at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, with Mousier Cardin, now 98, in attendance. The event also marked the 70th anniversary of Cardin's fashion house, and honoured filmmakers P David Ebersole and Todd Hughes, co-producer Cori Coppola and myself as the composer for the film.

What was the interview/selection process like? What do you believe set your application apart from others who may have applied for the role of film composer?

I had actually already worked with the directors and producers before on another feature documentary called Mansfield 66/67, which came out in 2017, and is a film about the last two years of actress Jayne Mansfield's life, and the rumours swirling around her untimely death.

The filmmakers, P David Ebersole and Todd Hughes, from Palm Springs, California, were Artists in Residence at the Northern Film School in Leeds for a year. I was a student at the time at Leeds Beckett University, and I managed to get on the project, co-scoring the entire film with my tutor at the time, Bob Davis. I learnt a great deal on that project and the filmmakers must have liked what I did because they asked me to score their next film a few years later which was House of Cardin. Although I made sure to keep reminding them that I was here! And now we’re actually working on our 3rd collaboration together, another feature documentary, this time on the late Trini Lopez called My Name is Lopez.

I guess the key thing to take from that is when you do land a gig, you want people to want to work with you again, when you finish. There’s lots that can go wrong on a project and people fall out over big and small stuff all the time. There’s usually a lot of money at stake, a lot of people’s time invested also and as the composer, you’re usually coming in at the end of the project in Post-Production. You want to be easy to work worth, help solve problems, write good music and have fun. When you build those relationships, you can develop a shorthand and a mode of communication that really helps when you’re under pressure, which will undoubtedly happen during any project. Moreover, when you have an existing relationship with filmmakers you can join the project much earlier in its development and help shape the film much more, which can be really satisfying from an artistic and musical point of view.

You wrote a score spanning the life of Cardin’s 98 year life story. What is your general research process when preparing to score a film and how did your approach differ when working on House of Cardin?

I like to create playlists on Spotify and YouTube of musical reference points. Creating my own temporary score, in a way. I don’t play these playlists to anyone else, or put the music to the film, as only I know why certain pieces of music are in the list. I also don’t want directors and producers falling in love with music that isn’t mine, you have a hard-enough task getting them away from their temp music let alone introducing them to more temp music that you like.

For example, I might like the rhythm or pace of one piece and the orchestration of another or the guitar pedal effects on one and the production approach of the drums for another. For a film like House of Cardin, it was the ideal collage of musical influences and time periods for my personal interests.

I grew up with an extremely eclectic collection of music being played in the house. On any given day I might have heard Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, Ice T’s O.G. Original Gangster Rap, Jimi Hendrix or Miles Davis. When you’re dealing with a subject like Cardin, and the 98-year history, you have a lot of contextual reference points and musical legacy to draw from and I think the resulting score is really diverse in genre as a result. For example, the film starts in Paris in the 1930s and 40s, so I drew inspiration from artists like Django Reinhardt & Stephane Grappelli, I tried to evoke Hollywood in the 1950s through jazz quartet arrangements and symphonic orchestrations, or the sound of the 1960s lunar era ‘Space Race’ through analogue synthesis, distorted guitars and electronic instrumentation. It was a really diverse approach to instrumentation, but the melodic and thematic ideas are maintained throughout, like most film music, influenced by operatic leitmotif and variation compositional techniques.

It’s also really important to draw from the narrative themes of the film and the characters too. For example, Cardin is a futurist and was huge in the 60s, so a lot of music has a very futurist production aesthetic while utilising 1960s rock instrumentation. Cinematic music can be whatever the film dictates and that can be really exciting. Each project can have a different approach and that’s what really drew me to film music in the first place.

What was it like working with directors P David Ebersole and Todd Hughes on the film? Are there any challenges involved in working with working directors on a score?

It’s always really great working with P David Ebersole and Todd Hughes aka The Ebersole Hughes Company. As previously mentioned, they gave me my first break and without that I may not have landed some of the other really amazing projects I’ve been lucky enough to be a part of – so I hold a great deal of gratitude towards them. I also get on with them really well outside of a professional capacity and I think that’s important sometimes.

There are always challenges collaborating with anyone and on any project. For example on House of Cardin, we were pushed for time toward the end to get the score and film finished for the festival premiere in Venice and that can get quite stressful, but we all get on really well and have worked together before so we knew we’d get there – there was trust already established which was reassuring.

On other projects, with other people, it can be more difficult sometimes but it’s important to remember that when you’re working on a film, you are serving the film and the director’s vision – or the showrunner’s vision on a TV series. That can be difficult to adjust to for new composers. Leave your ego at the door. Hopefully you can bring yourself to the project and be artistically satisfied but know that the film is the most important thing. I’ve had some tough experiences where I’ve disagreed with directors but they’re almost always right! I look back at some projects that could have gone badly but the resulting score is always something I’m really proud of, because it’s a result of a collaboration between people who really care about what they are doing. These days I’m more used to the diplomacy side of the job and expect things will go wrong at some stage but more often I‘m working with great people and building long-lasting relationships. As you become more experienced it becomes less stressful and you trust the process more.

You worked on the score with a full symphony orchestra. What is your personal composition process when working with an orchestra of this size and how do you ensure your vision gets translated in the right way?

I usually write a bunch of ideas on the piano or guitar just to get the creative juices flowing. Sometimes I’ll pull up a patch of sampled strings on the computer to ‘sketch’ with. I usually start with a main chord progression and improvise melodies on top until I find something I like. Sometimes it’s the other way around and I have a melody in my head and then I construct harmony and chords around that melody.

Once I’ve got the tune, I then begin to orchestrate straight into the computer using sampled instruments. I like to hear the orchestrations I’m doing while I’m composing, I’m doing both at the same time often, so the samples really help with that. Sometimes it’s easier to see the orchestration visibly, as MIDI notes in a piano roll or notated on paper but I almost always start orchestrating on the computer.

Sometimes I write directly to a scene and other times I write away from the picture and sync it later. Once I’ve got a solid composition and orchestration down, I send the files to orchestrators who prepare the score and notate all the parts for the musicians to read. Sometimes you do everything yourself but more often, on bigger projects, it’s a team effort. It’s important you work with orchestrators who know your style, who you can communicate effectively with. I worked with a previous student and lecturer at Leeds Conservatoire, Alistair Kerley, and another orchestrator, Paul Taro Schmidt, to prepare the notation for House of Cardin.

The technology is so good and helpful these days that you can get a pretty clear idea of how it is going to sound on the recording stage when you’re mocking up demos with sampled virtual instruments. This really helps get directors and producers on board with your ideas as well, but you can never beat the real thing. Samples are great but they’ll never replace real musicians, playing live, it adds so much.

You mixed the film with Academy Award and BAFTA winning sound mixer, Ben Wilkins. What did you learn from your time working with Ben? How important was it to the scores success for you to be involved from the early composition stage through to the final mixdown?

Again, I had previously worked with Ben on Mansfield 66/67 and we got on really well. So, I was excited to be back working with him for House of Cardin. He’s British but has been over in Hollywood for 25/30 years. As you mention, he’s won an Academy Award, a BAFTA and an AMP award, for his work on the film Whiplash (2014), amongst numerous other accolades, and has worked on some of the best Films, TV shows and now streaming series such as Star Trek, The Walking Dead, The Sopranos and more. To work with someone of that calibre is truly inspiring.

He’s actually become somewhat of a mentor and has taught me a great deal about working at that level. It’s the attention to detail and time that you commit to the work that really shines through in the end. He also showed me the ropes when I landed in LA and has been really supportive of my career so far, helping promote me and my work wherever possible and introducing me to various film industry personnel over there. We’re really good friends now.

I personally think it’s important to be involved from as early as possible through to the final mix. Most composers won’t be at the final mix and in all honesty, sometimes you’re not really welcome as the composer. There are enough things to do without the composer being egotistical about the volume of the score for example. But that wasn’t the case working with Ben. Again, we’re really good friends now and we’ve got a great working relationship. We’re there to serve the film. Usually the music editor will be at the dub/mixing stage as the composer is too busy on other projects or working on the next episode or making revisions to other cues, but if possible I like to be there and I like to fill the role of the music editor where possible.

A lot can change during the mix. It’s often the first time everyone is hearing everything together: the dialogue, foley, sound design, and music. You often have to make quite drastic changes to the music, completely re-write cues, or heavily edit them. A music editor usually does this but I prefer to be there so I can have more creative control over what happens to the score. Not to be overprotective of the music, but to just ensure that if any changes are needed, I’m not hearing it for the first time at the premiere…

Great music editors will do a great job, and some directors don’t want you at the mix, so it really depends on what each project is like, but certainly with Ben, P David and Todd, we like to work very closely together. Plus, who doesn’t want to go to Hollywood?

What three bits of advice would you give to current students moving towards a career in film music composition?

Getting noticed or securing your first gig can be difficult but I constantly put myself in positions where I could be noticed, and I often wasn't but you keep trying and eventually people will take notice. So...

- Be proactive. No one is going to promote you on your behalf until you get to a certain level, so put yourself out there, attend events, screenings, network with filmmakers, not composers. I hung out with student filmmakers when I was a student, I scored their films for practice. Some of those films got shortlisted for BAFTAs or nominated at the Academy Award Student Oscars, so you never know where an opportunity will take you. Composers don't get you gigs unless you're assisting them. It's much more fruitful to network with filmmakers, picture editors and music supervisors.

- Build relationships with people. Even if you're working with really difficult people, which thankfully doesn’t happen to me very often, it is much better to be the person who deals with that well and gets recommended by others for diplomacy. The director or producer may be an absolute nightmare, but the editor may have seen how you dealt with it or liked your music and recommends you to another producer, so always be pleasant to work with!

- It's important to try and develop your own artistic voice. This can be hard to know if you're doing it right and it's probably something that we'll all be searching for, for all of our lives. However, we all have very different backgrounds, musical influences, inspiration etc. and if you feed all of that into your music, you will undoubtedly come up with something that reflects the unique combination of inputs. Don't try and sound like another composer. There are plenty of people out there trying to sound like Hans Zimmer or John Williams but, in my opinion, no two Hans Zimmer scores are the same. He's constantly reinventing his musical style, approach and every score has a unique set of reference points and inspiration that is true to the film and the story of the film. Don't actively try and sound the opposite of what other people are doing either. I would just say, be yourself...everyone else is taken.

Find out more about James Peter Moffatt and House of Cardin via their respective websites.

Find out more about Film Music at Leeds Conservatoire.